linescape

installation mixed media 2016

intro

linescape, 2016, Courtesy Galerie Georg Kargl, Vienna

Herwig Turk’s work linescape, aims at a revision of the cliché-laden reception of 1960s and ‘70s American Land Art, the historiography of which is, to this day, dominated by the study of the monumental Earth Works by artists such as Robert Smithson, Michael Heinzer or Walter De Maria. He confronts an icon of Land Art, Robert Smithson’s monumental earth sculpture Spiral Jetty with photographs which document, that the deserts in the southwestern USA had, long before the Land-Art artists had discovered it for themselves, been technologically moulded by human interference such as the extraction of natural recourses, or use as a military testing ground by the American army.

Installation

top left:

Landscape = Laboratory, MMKK Museum Moderner Kunst Kärnten, Klagenfurt/A 2014

photo: © Gebhard Sengmüller

top right:

linescape, Georg Kargl Box, Vienna/A 2016

photo: © Gebhard Sengmüller

middle left:

linescape - detail, Georg Kargl Box, Vienna/A 2016

photo: © Peter Paulhart

middle right:

linescape - detail, Georg Kargl Box, Vienna/A 2016

photo: © Herwig Turk

bottom left:

linescape - detail, Georg Kargl Box, Vienna/A 2016

photo: © Herwig Turk

bottom right:

linescape, Georg Kargl Box, Vienna/A 2016

photo: © Gebhard Sengmüller

Landscape = Laboratory, MMKK Museum Moderner Kunst Kärnten, Klagenfurt/A 2014

photo: © Gebhard Sengmüller

top right:

linescape, Georg Kargl Box, Vienna/A 2016

photo: © Gebhard Sengmüller

middle left:

linescape - detail, Georg Kargl Box, Vienna/A 2016

photo: © Peter Paulhart

middle right:

linescape - detail, Georg Kargl Box, Vienna/A 2016

photo: © Herwig Turk

bottom left:

linescape - detail, Georg Kargl Box, Vienna/A 2016

photo: © Herwig Turk

bottom right:

linescape, Georg Kargl Box, Vienna/A 2016

photo: © Gebhard Sengmüller

text

Linescape 2016

In his installation Linescape, specially conceived for Georg Kargl’s BOX, Herwig Turk addresses himself to a reappraisal of the history of the development of one of the most radical art concepts of the 1960s: American Land Art. In contrast to Minimalism, which was concerned with objectivity and could be found primarily in the gallery and museum context, Land Art was seen as a romantic art movement, but one that was explicitly critical of society.

Landscape was not used as attractive background for the positioning of sculptures; landscape itself became a work of art. The interventions were to be bold. Heavy equipment was used to radically intervene in the landscape, and large-scale works were constructed in a durable form that often required decades to develop and become finalized, the process in some cases lasting up to today. One of the best-known works of American Land Art is Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty in Utah’s Great Salt Lake: a coil approximately 500 meters long made of rocks, algae and salt, completed in 1970 and still visible today – although worn down by erosion.

Even today, the works of proponents of Land Art are seen in art history as a form of social criticism, as artistic statements made by a male-dominated group, which was no doubt inspired as much by the vast American landscapes as by the prevailing mood of awakening of a victorious nation after World War II and the inflated self-confidence that went with it. Rarely, however, are parallels drawn between the ways in which the American desert landscape has been approached and used by the US military, on the one hand, and by artists of the Land Art movement on the other. It is to this neglected yet fully comprehensible aspect of history that Herwig Turk seeks to draw attention in his installation, taking Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty as an example and using that work as a basis for discussion.

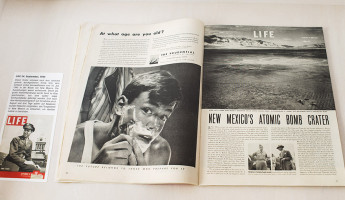

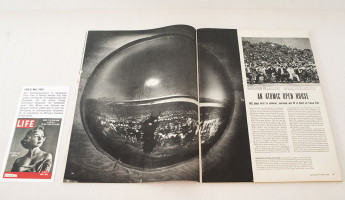

Two photographs designed as wall scrolls and hung in a corner constitute a 360-degree panorama view of the Spiral Jetty. Hanging from the ceiling above them are five silkscreen prints showing US Army target installations in the UTTR restricted zones, which are located in close proximity to Utah’s Great Salt Lake. In addition, displayed in an elegant, flat top display case are three issues of Life Magazine dating from 1945 to1952, which give telling evidence of how broadly information concerning the initially secret atomic bomb tests had managed to spread through American popular culture, thus making it possible for the media to massively publicize the military strength and supremacy of the American superpower during the Cold War. The desert was stylized, so to speak, as an atomic laboratory. So by no means were the American artists of the Land Art movement utilizing “untouched” virgin landscapes to stage what eventually established their artistic identity; rather, in the course of the atomic tests, these sites had long mutated into an “atomic desert” in the mass media. Herwig Turk’s installation can be read as a reflection on reporting in the mass media, which was of immense political, economic and ecological significance. Turk clearly demonstrates that even the scientific writing of history is interpreted along subjective, ideological lines, that it is subject to constant change, and that it is constantly being reconstructed.

Fiona Liewehr, Vienna 2016